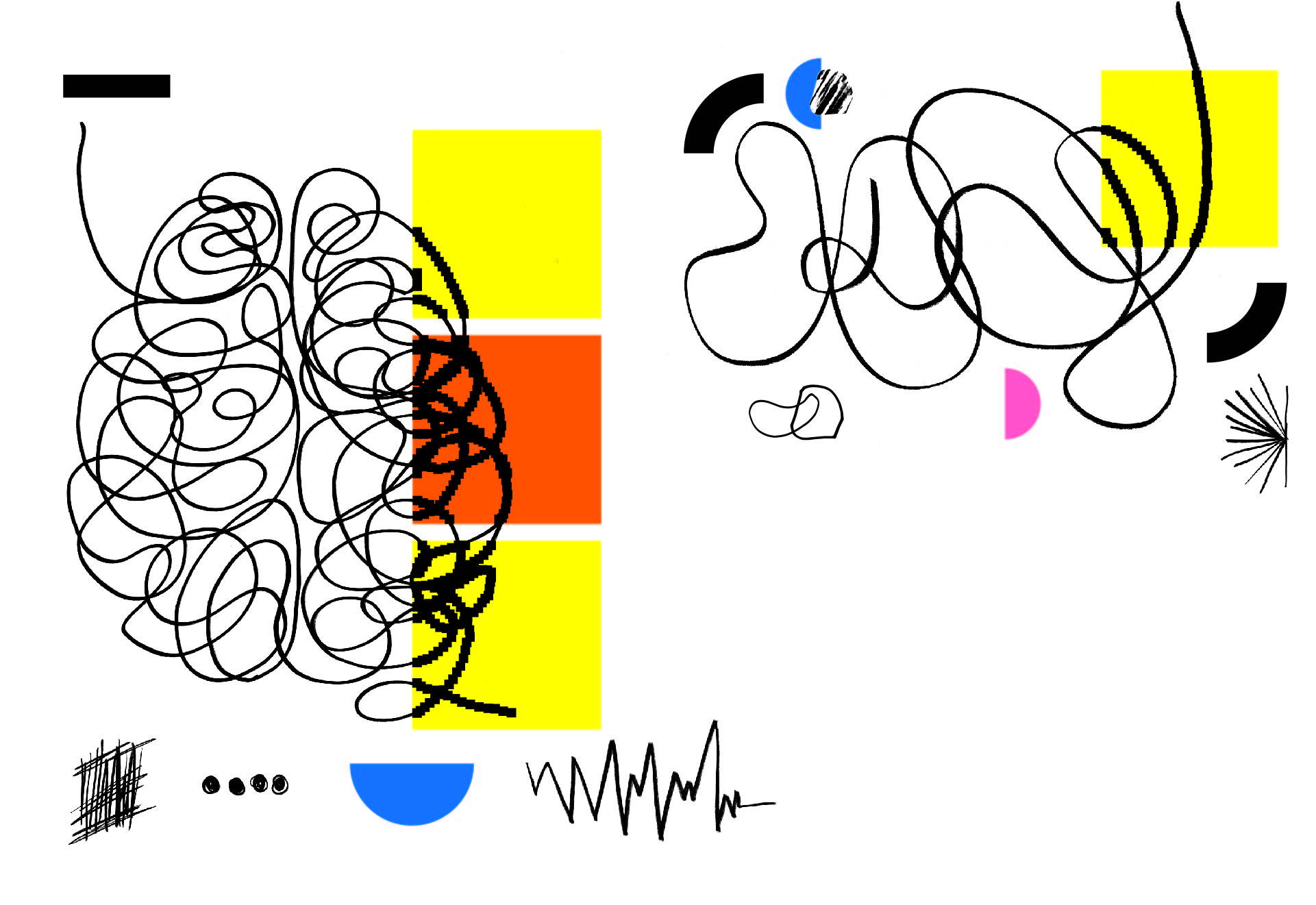

We often assume that the brain is split into the logical left side and the creative right side. That’s wrong, says Scott Barry Kaufman the scientific director of the Imagination Institute and a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania. When the brain starts a creative pursuit such as sketching, neurons in different sections start snapping. Sketching is so powerful because it turns on what Kaufman calls the Imagination and Salience Network and silences the Executive Attention Network, getting different parts of the brain to focus on improvisation, ambiguity, and making connections. Sketching flips the brain into a flow state: think of a rapper mid-freestyle, or a jazz musician gliding through a solo.

These aren’t the only ways sketching lights a creative fire. Jeffrey Wammes, a researcher at the University of Waterloo Department of Psychology, has found that sketching creates more cohesive memory and connects visual, motor, and semantic information. The quality of the sketch didn’t matter. Even though laying out ideas on paper frees the mind to improvise, the act of creating the image helps preserve and process. Wammes’s experiments found that even a few seconds of sketching bolstered a subject’s memory.

Consider Picasso’s famous Guernica, an iconic piece of 20th century art. The mural started as a series of sketches, where the artist shuffled through dozens of concepts and layouts to arrive at his famed anti-war statement. It was “Darwinian creativity,” a series of experiments and occasional dead-end paths that came together in the end to create a masterpiece.

The boost in processing power also helps designers, teams, even artist’s ability to synthesize and assimilate. The creative consultancy IDEO brainstorms with easel-sized Post-It notes, generating a literal paper trail of creative debate, deliberation, and production, helping participants recount the road to a breakthrough.

Turkish researcher Zafer Bilda discovered in repeated trials that designers who use paper to sketch “changed their goals and intentions more frequently and engaged in a higher number of cognitive actions” than those using software, leading to a more versatile approach. The rough roadmaps laid down on page after page perhaps couldn’t have been realized any other way. There’s a reason artists and designers list pencil and paper as their favorite brainstorming tool. Perhaps, like Hadid, they understand that the road to a great idea is never one single, simple straight line.