The Artifacts of Connection

Artifacts engage our senses, pique our curiosity, and punctuate our lives. In fact, the English word “souvenir” comes from the French verb “to remember.”

This article was originally published in Issue 12 of the Mohawk Maker Quarterly. The Mohawk Maker Quarterly is a vehicle to support a community of like-minded makers. Content focuses on stories of small manufacturers, artisans, printers, designers, and artists who are making their way in the midst of the digital revolution. Learn more about the quarterly here.

Suggested Articles

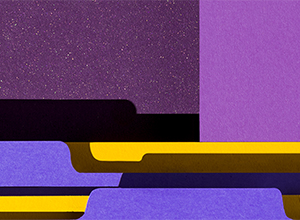

In today's competitive marketplace, packaging plays a crucial role in brand perception and consumer satisfaction.

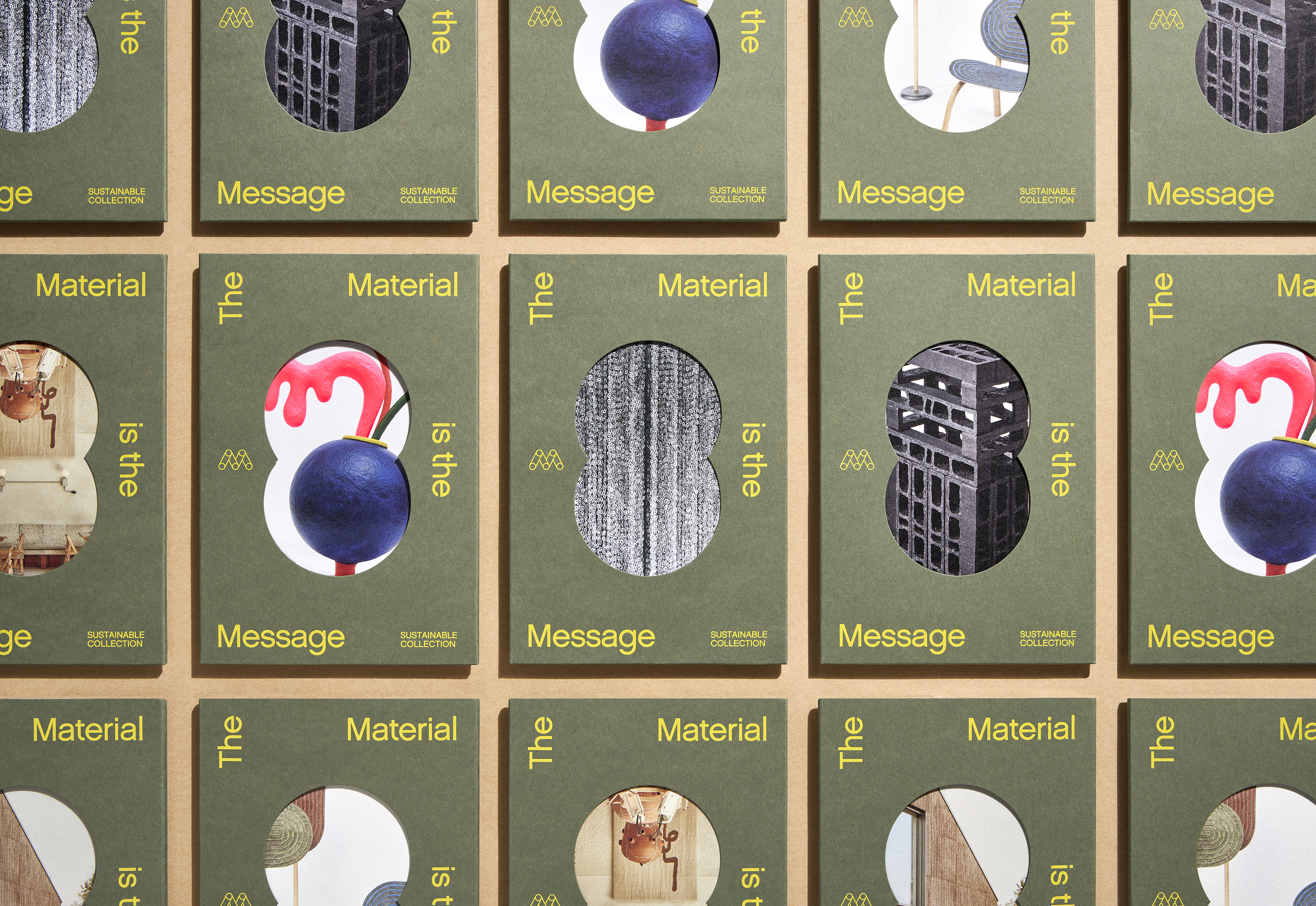

Mohawk Renewal marks a bold new chapter in our ongoing commitment to sustainability and innovation in papermaking.

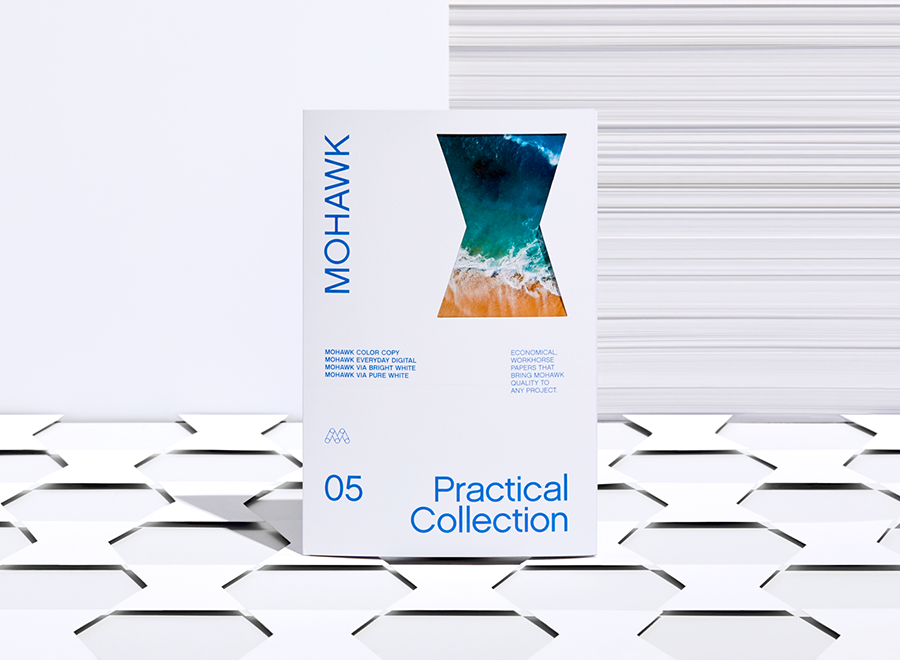

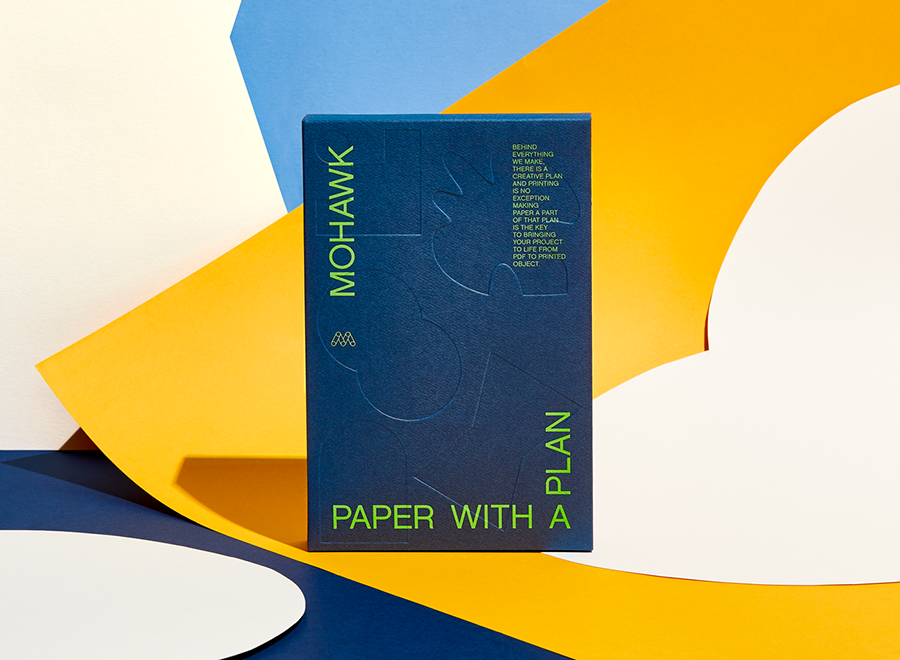

Beautiful. Effective. Memorable. What will you make today?